Feature: Bike Race Cancellations Through History

Feature: Bike Race Cancellations Through History

What has caused cycling races to be cancelled in the past? We take a look at what the sport has weathered and what that means for us today.

Unlock this article, live events, and more with a subscription!

Already a subscriber? Log In

We call the sport’s oldest races “monuments,” a title earned by their resilience. Born in prewar Europe, these races survived the chaos that followed and even grew stronger.

Take, Liege-Bastogne-Liege, modern cycling’s oldest race. The event now christened La Doyenne (the old lady) began in 1892 as an amateur race, and was run just three years before interruption. Between 1895 to 1911, Liege was held only intermittently, but during that same time period, the sport of professional cycling was born.

Il Lombardia, known as the race of the falling leaves finished in a sprint in its 1911 inaugural edition.

In 1903 the Tour de France was christened, and in 1905 Italy joined the party by introducing Il Lombardia and then in 1907, Milano-Sanremo.

The youngest monument, Ronde van Vlaanderen (Tour of Flanders) arrived in 1913, by which time cycling had taken a firm hold in western Europe.

However, the entire continent was soon to be engulfed in War.

Amidst these tumultuous times in the sport, let’s take a look back at some of cycling’s most historic races — the storms they weathered, and those they could not.

War Time

Some three months after the second edition of the Tour of Flanders, on June 28, 1914 Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne along with his wife Sophie were assassinated. It was the spark that ignited one of the world’s most deadly conflicts.

Much of the European continent would be engulfed in war until the end of 1918, and indeed the epicenter of bicycle racing would be greatly affected.

Cycling was a young sport at the time, but it would prove to be far from weak.

During World War I, the entire Flemish region served as the western front. German forces clashed with French, British and American troops, and the Tour of Flanders could not (officially) be held.

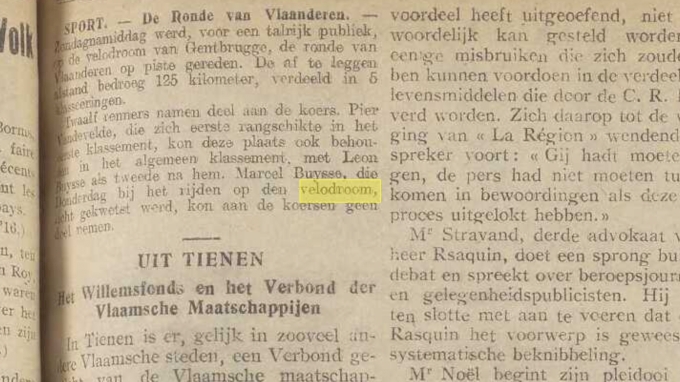

Uncovered newspaper clippings however suggests the tenacious organizers of the Tour of Flanders abandoned the Flemish Ardennes and held an understated Ronde van Vlaanderen on a velodrome in Gentbrugge in 1916. Though the race was only half as long, at 125 kilometers.

Newspaper archive from Het Vlaamsche Nieuws – July 26, 1916

Other race organizers similarly pushed their luck and found ways to hold their events during the first World War. The twelfth edition of the Tour de France began very the day Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and while the continent’s entangled alliances pulled France towards war, the 15 stage race was seen to completion. The Tour de France would not be held again until 1919 after the conclusion of the war.

Italy’s Milano-Sanremo would only be called off once during World War I and Il Lombardia would go on uninterrupted throughout the entirety of the war. In fact, in its 119 year history, Il Lombardia was only called off twice—in the final two years of World War II. Less than two months after the Japanese surrendered, racing returned to Lombardia.

Belgium was a victim of geography as much as anything else during the World Wars. After suffering unprecedented devastation in World War I, Belgium found itself once again standing between a German army and France. As the continent again descended into war, the Tour of Flanders marched on in 1939 and 1940. Months after the 1940 edition however, Belgium was invaded by German troops marching for France.

Escorted by soldiers, Belgians leave their homes as German troops advance towards France.

After 18 days of fighting, Belgium surrendered to Germany and would remain an occupied nation for the next five years. Yet, somehow the Tour of Flanders lived on.

In 1941 and every year after for the remainder of the war, the Tour of Flanders would be held with cooperation from occupying German forces.

Paris Roubaix was called off the first three years of the second World War, but amazingly it returned in 1943 to travel the 250 kilometers from Paris to the velodrome in Roubiax.

The monument would return every year for the remainder of World War II.

Bike Racing, Weather Or Not

How races and riders respond to weather has changed over time.

Milano-Sanremo earned a reputation early on as an epic venue for a race. In 1910 a snowstorm ripped across the route, forcing racers to seek shelter in towns and villages along the course.

Of the 63 starters that day, four riders would finish the 289 kilometer race. Frenchman Eugéne Christophe won in a time of 12 hours and 24 minutes.

Fast forward 103 years and snow once again punished the peloton along the road to Sanremo. In 2013, riders would be driven out of the storm on busses and restarted, a maneuver which shortened the race to 246 kilometers.

When faced with protests from riders before the start of the 14th stage of the 1988 Giro d’Italia, the race director simply said that the first riders to arrive in Bormio would get their pick of the hotel rooms, and presumably the hot water that came with them. With that, he sent riders into a blizzard on one of Italy’s highest peaks. Undeterred, Andy Hampsten attacked on the lower slopes of the Passo Gavia and would go on to become the first and only American to win the Italian grand tour.

The snowstorm on the Stelvio caused chaos and confusion during stage 16 of the 2014 Giro d'Italia.

In 2016, the UCI introduced the extreme weather protocol, which allows any race’s “stakeholders” to discuss alternative plans of action, should the weather forecast predict complications.

While the sport has certainly become more professionalized since the days of seeking shelter in cottages along the road to Sanremo, it hasn’t actually changed that much.

History tells us that race organizers rarely make concessions when the weather bares its teeth, and those riders who persevere through the harshest conditions are often richly rewarded—their heroic rides told and retold until the stories become legends.

Disease During A Different Time

In the final year of World War I humanity faced another challenge, which by some counts proved even more deadly.

In 1918, the world suffered from a pandemic known as the Spanish Flu (note: despite the name the origin of the virus remains unknown). As soldiers from around the world fought in trench warfare, suffered in crowded hospitals, and then returned home to their various countries, the disease spread around the globe.

By some extreme estimates the 1918 flu pandemic killed as many as 100 million people, yet as soon as World War I ended, cycling races not only resumed in Europe, they flourished.

In the years between World War I and World War II, the monuments would become cemented in the culture of the sport. As Belgium rebuilt its ravaged infrastructure, cobblestones were the cheapest material available to pave the roads throughout the countryside.

These cobblestone roads reconnected war-torn towns and cities, and are the very roads that Paris-Roubaix and the Tour of Flanders revisit year after year. Even though the Spanish Flu would hit the global population in multiple waves before finally fading away in 1920, the races went on.

In Conclusion, The Coronavirus

So where does that leave us in 2020? The coronavirus has already caused the cancellation of three major Italian cycling events including Milano-Sanremo, a race that withstood World Wars.

With the coronavirus casting an ever darkening shadow of doubt on daily life, what can we learn from a sport that’s withstood everything man and nature could throw at it for 128 years?

A sprint for nobody. The 2020 Paris-Nice is raced despite crowd restrictions put in place by French authorities.

The days of sending a peloton over the Gavia in a blizzard are behind us. Similarly, knowledge about public health far exceeds our medical knowledge circa 1918.

Now a global sport, cycling thrives on an interconnected world and so do infectious diseases. Race organizers are relying on their governments for clarity on how to proceed, whether that means banning fans from finishes as in Paris-Nice or having to cancel the events all together.

But if cycling’s history can teach us anything, in spite of it all, the show can and will go on.