The 90-Year-Old Doper Is Not A Doper At All: The Carl Grove Case

The 90-Year-Old Doper Is Not A Doper At All: The Carl Grove Case

Beyond the news of a 90-year-old doper is the story of an athlete defying his age, of a community of supporters and of a double liver dinner.

On Friday, Jan. 4, the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency issued a press release that a 90-year-old, world record setting cyclist had failed a drug test.

The press release stated that Carl Grove of Bristol, Indiana, had tested positive for the anabolic agent epitrenbolone at the Masters Track National Championships in July of 2018.

In investigating Grove’s case, USADA determined the positive test was “more likely than not” due to the consumption of contaminated meat. Grove was given a rare public warning, and stripped of the world record he set at Track Nationals.

Every major cycling publication—along with international outlets such as USA Today and the BBC—published the story, which went viral.

Reactions online ranged from indignation to amusement: From outrage that the anti-doping surcharges tacked onto USA Cycling licenses were used to nab a 90-year-old amateur, to concerns that cycling (yet again) was living up to its reputation as the world’s dirtiest sport.

Even Lance Armstrong offered up some snark in response to the news, writing on Twitter, “By golly, we’re gonna clean up this fucking sport, if it’s the last thing we do!”

But beyond the sensational nature of a 90-year-old doper, is the story of an elderly athlete defying his age, of a community of coaches, friends and family and of a double liver dinner.

This is that story.

***

In 2009, Carl Grove showed up at a training camp organized by cycling coach Tim Cusick in the rolling hills of southern Pennsylvania. Grove, who was then 81 years old, had done some competitive cycling in his 20s, but told Cusick, “I was never that good.”

After a 55-year break from the bike, he’d decided to start riding again.

“We were like, holy crap, we’ve got an 80-year-old guy coming to camp, how are we going to deal with this?” Cusick recalls. “We had all these contingency plans. We had assigned one coach to just follow Carl around and make sure he was safe and he didn’t die.”

Of course, Cusick says, “The guy shows up to camp and he’s fast as crap.” Grove had no problem keeping up with the camp’s other competitive riders.

Cusick sat down with Grove and said, “Carl, you’re amazing, you need to be racing.”

Grove hedged, at first. With all his kids, grandkids and great grandkids, he felt he wouldn’t have time. “I’m beyond it,” he told Cusick.

Think about it, Cusick responded, “You could be a role model.”

Not long after Grove called Cusick out of the blue. “I’m 82 years old and it’s about time I started pursuing some of my own dreams,” he told Cusick.

Grove said it was important that he set an example for the elderly community, that you didn’t have to get sedentary, go into an old age home and die. He wanted to show people that if you took care of your body and remained active, you could extend your life.

Cusick built Grove a training program, and they got to work.

***

Grove trained 12 solid hours a week, and says Cusick, “got really fast.”

In 2010, Grove went to the Masters National Road Championships in Louisville, Kentucky, and won the 20 kilometer time trial by eight minutes. (Yes, eight minutes.) That evening, he called Cusick to discuss his strategy for the road race. “He calls me all nervous,” recalls Cusick, “And I’m like, Carl, you just won the time trial by eight minutes, here’s the strategy: When the guy shoots that little gun, just pedal as hard as you can and everything will work out.”

Over six laps on a hilly five-mile circuit in Louisville’s Cherokee Park, Grove averaged 20 miles per hour. He won by 17 minutes and nearly lapped his closest competitor twice.

From there, Grove set his sights higher. He trained for the Masters Road World Championships in 2011, and won the time trial in the 80 to 84 age group by three minutes.

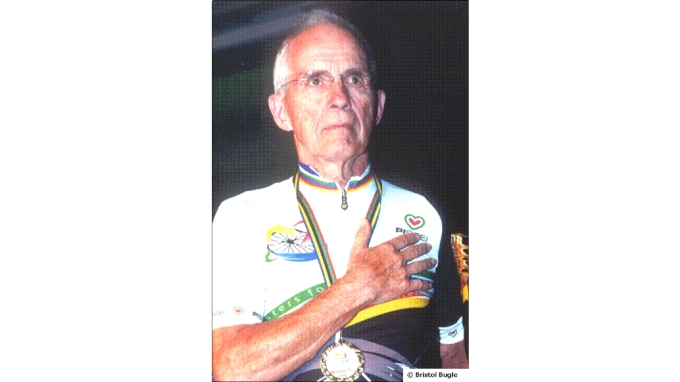

As Grove stood on the podium and listened to the national anthem play, he told Cusick it was the proudest moment of his life.

This, from Grove, a military veteran who spent his life playing in the U.S. Naval Band, who performed in the White House for Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy and traveled the world with the likes of Bob Hope, entertaining American troops as part of the USO.

But as fast as Grove could ride, he couldn’t completely outrun his aging body. “He can’t see, and he really can’t hear,” says Cusick. Grove suffered a couple crashes while out training near his home in Indiana, and eventually his support group, his friends and his family, intervened. They convinced Grove to take his training indoors, setting him up on a stationary bike in the basement. Grove also decided to switch his focus to track racing. He felt the more consistent surfaces of a velodrome would provide a safer competitive environment.

Though Grove had never ridden in a velodrome, or on a track bike (no brakes, no freewheel, no gears), he began setting athletic goals. Approaching 90, and with no competitive peers, really, to test himself against, Grove and his support group set their sights on world records.

For a world record to be recognized, at any competitive level in cycling, the athlete’s equipment must be certified by a race official (no hidden motors) and the athlete must submit to drug testing. Grove and his support group reached out to the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency and asked them to come to the 2018 Masters Track National Championships in Pennsylvania.

Then, Grove began working toward setting the 90-year-old world record.

***

In Grove’s first competition at the Masters Track National Championships, the 500 meter time trial, he covered the distance at a speed of 23.8 miles per hour and set the world’s best time at 47.8 seconds. An official certified his bike and he took a drug test, which he passed.

That evening, Grove went out to dinner with his friends, including Cusick’s wife, Kathy Watts, who is also a coach. Cusick wasn’t at the 2018 Masters Track Nationals and no longer formally coaches Grove, but he and his wife remain close friends with Grove.

At dinner, Cusick says, “Carl gets this double liver dinner.” He pauses as he talks, emphasizing the words “double” and “liver.”

“He’s 90, right?” says Cusick. “This is what he grew up on and that was his big reward dinner.” The liver also happens to be the place where, if an animal was being given an anabolic substance to promote muscle growth, the metabolites of that substance would likely be found. The liver moves waste out of an animal’s body, kind of like a garbage truck.

“Literally, 10 years ago, I had warned him against eating it,” Cusick says.

But Grove is 90. He’d just set a world record. And if he wants to eat a liver dinner, who is going to tell him he cannot eat a liver dinner?

The next day, Grove lined up and raced the two kilometer individual pursuit. Again, he set a world-best mark with a time of 3:06. His bike was certified, and he was tested.

This time, though, Grove failed the drug test.

***

“Right from the get go, USADA knew they had a PR nightmare on their hands,” says Cusick.

Sanctioning a 90-year-old racer who unknowingly ingested a performance enhancing substance would make the Agency look overbearing and absent of common sense. However, not sanctioning Grove would call into question the global system of anti-doping that USADA abides by, and potentially delegitimize the Agency’s authority.

“They had their highest people on this,” says Cusick. “They really looked deep.”

Cusick remains complimentary of the way USADA handled the case, despite the pain of the entire episode for Grove and his community of supporters. (Grove has declined to speak publicly about the positive test, and asked Cusick to represent him.)

Normally an athlete is solely responsible for proving the invalidity of a positive test, but Cusick says USADA helped Grove have his supplements independently tested for steroid contamination, and even visited the restaurant where Grove ate the night before his test.

Because only trace amounts of epitrenbolone were found in Grove’s test—picograms, not nanograms—and because Grove provided a clean sample just one day prior, USADA determined that the source of Grove’s positive test was “more likely than not” caused by the liver dinner he’d eaten the night prior.

USADA also found one of the supplements Grove was taking contained the banned substance clomiphene, though that substance did not show up in Grove’s test at Nationals.

Grove received a public warning from USADA and was stripped of both his national title and world record, an extremely light sanction in comparison to those handed down to elite athletes in similar circumstances. (Take Alberto Contador’s clenbuterol case, for example.)

Grove is free to race again, to chase more records. But, at 90, where does he go from here?

***

“He’s absolutely crushed,” Cusick says of Grove’s current state.

Cusick says when Grove first found out about the positive test, about the tainted meat and the contaminated supplements, he felt terrible. “Tim, did this help me?” Grove asked Cusick.

“He was afraid he cheated,” Cusick says.

Grove had no interest in fighting the sanction, says Cusick, “Because he wanted to make a good example, that if you make a mistake, you have to own it.”

Cusick says he had warned Grove multiple times against taking supplements, which he says Grove took not for athletic reasons, but because he was fearful of losing his mental acuity. Grove was easily swayed by the unsubstantiated online claims of supplement manufacturers.

The message that both Grove and Cusick hope comes from Grove’s sanction is that athletes are ultimately responsible for what’s in their bodies, at any level in the sport.

Will Grove compete again? Cusick hopes so. “I’m telling him, 'Let’s go, let’s set some more goals.' This isn’t about doping or not doping, it’s about staying motivated.”

The age-group hour record is well within Grove’s reach, says Cusick. “He could get off the couch tomorrow and set that.”

But for the record to be valid, Grove now knows, he must pass a drug test first.